El pasado es un animal grotesco. Ideologías de la memoria urbana en el Belgrado postsocialista

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.54104/nodo.v16n32.1352Palabras clave:

estudios post-socialistas, memoria colectiva, modernismo yugoslavo, patrimonio arquitectónico, ruinas urbanasResumen

Este ensayo nace de la visión de las monumentales ruinas de los edificios de la extinta Yugoslavia, en Belgrado, capital de la república de Serbia. Los edificios fueron bombardeados en 1999 por las fuerzas de la OTAN (Organización del Tratado del Atlántico Norte), comandadas por Estados Unidos. Dos décadas después se encuentran aún sin reconstruir o demoler. Ruinas como las del Generalštab (edificio del Estado Mayor yugoslavo), ubicado sobre la diplomática avenida Kneza Milosa, generan una gran controversia pública sobre su destino. Esta situación sirve como detonante para realizar una serie de reflexiones acerca de la historia reciente de Yugoslavia y el componente urbicida de las guerras balcánicas. También abre la puerta al cuestionamiento acerca de los resortes ideológicos en la construcción de la memoria colectiva. En el caso del Belgrado post-socialista, las ruinas se han usado de manera propagandística para la victimización nacionalista. Sin embargo, paradójicamente también inducen a preguntas incómodas para las autoridades serbias, sobre el pasado y sobre el futuro. El ensayo analiza algunos sucesos importantes en la planeación urbana del Belgrado socialista y la potencia de ese proyecto en tanto “utopía concreta”. Compara aquellos hitos urbanísticos con la situación actual. También es un homenaje a la figura de Bogdan Bogdanović, arquitecto serbio y último alcalde del Belgrado socialista, uno de los últimos utopistas urbanos del siglo XX.

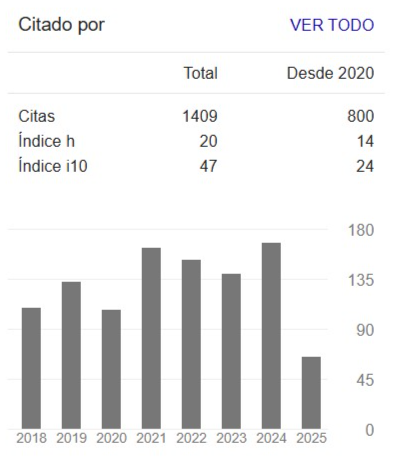

Descargas

Citas

Achleitner, F. (2009). Bogdan Bogdanovic: the doomed architecht. Catálogo de la exhibición: Bogdan Bogdanovic. Memorie and Utopie in Tito-Jugoslawien. Architekturzentrum Wien.

Alexander, S. (1979). Church and State in Yugoslavia since 1945. Cambridge: CUP.

Bădescu G. (2019). Making Sense of Ruins: Architectural Reconstruction and Collective Memory in Belgrade. Nationalities Papers, 47: 182-197, doi:10.1017/nps.2018.42.

Biserko, S. (2012). Yugoslavia’s implosion. The fatal attraction of serbian nationalism. Belgrado: The Norwegian-Helsinki Committee.

Blagojevic L. (2007). Novi Beograd: osporeni modernizam [New Belgrade: Contested Modernism], Beograd: Zavod za udzbenike, Zavod za zastitu spomenika kulture grada, Arhitektonski fakultet, pp.137-138.

Blagojevic, L. (2018.) The problematic of a “New Urban”: The right to New Belgrade. En: S. Bitter & H. Weber (edit.). Autogestion or Henri Lefebvre in New Belgrade. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Bloch, E. (2007). El principio esperanza. Madrid: Trotta, vol. 3. Publicado originalmente en 1975.

Bogdanović, B. (1993). Murder of the City. The New York Review of Books, 40:10.

Bogdanović, B. (1995). The City and Death, en J. Labon (ed.). Balkan Blues. Writing out of Yugoslavia, Illinois: Northwestern University Press.

Bogdanović, B. (2008). Rencontré européenne no. 7 (Entrevistado por A. Mirlesse). París: febrero de 2008. http://www.institut delors.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/etud82-fe-rencontres-europeennes_0.pdf

Boym, S. (2015). El futuro de la nostalgia. Madrid: Machado Libros. Publicado originalmente en 2001.

Coward, M. (2008). Urbicide: The politics of urban destruction. London: Routledge.

Čomić, Đ., y Vićić, S. (2013). National and tourist identity of cities the case study of Belgrade. Quaestus-Multidisciplinary Research Journal, pp. 15-27.

Eric, Z. (2018). The Third Way: The Experiment of Workers. Self management in Socialist Yugoslavia. En: S. Bitter & H. Weber (edit.). Autogestion or Henri Lefebvre in New Belgrade. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Freud, S. (1992). Lo ominoso. En Obras completas, 17, 1917-19. Publicado originalmente en 1919.

Fridman, O. (2015). Alternative calendars and memory work in Serbia: Anti-war activism after Milošević. Memory Studies, 8(2), pp. 212-226.

Gajevic, L. (2011). New Belgrade urban fortunes: Ideology and practice under the patronage of state and market. Tesis para obtener el grado de maestro. Máster universitario en gestión y valoración urbana. Barcelona: Universidad Politécnica de Cataluña.

Halbwachs, M. (2004). Los marcos sociales de la memoria, vol. 39. Barcelona: Anthropos Editorial.

Hatherley, O. (29 de noviembre 2016). Concrete clickbait: next time you share a spomenik photo, think about what it means. The Calvert Journal. https://www.calvertjournal.com/articles/ show/7269/spomenik-yugoslav-monument-owen-hatherley.

Hoepken, W. (1999). War, memory and education in a fragmented society: the case of Yugoslavia. East European Politics and Societies, 13(1), pp. 190-227.

Homer, S. (2005). Jacques Lacan: una introducción. Madrid: Plaza y Valdés. 2016.

Kulić, V. (2015). Yugoslavia In-Between (An Interview). En: Recentering Periphery: Imagined and Built Landscapes. http://www.recentering-periphery.org/yugoslavia-in-between.

Kulić, V., y Stierli, M. (2018). Toward a Concrete Utopia: Architecture in Yugoslavia, 1948-1980. Nueva York: Museum of Modern Art.

Le Norman, B. (2008). The modernist city reconsidered: changing attitudes of social scientists and urban designers in 1960s Yugoslavia. Tokovi Istorije, 3-4/2008, p. 149.

Lefebvre, H. et al. (1986). International competition for the New Belgrade urban structure improvement. En: S. Bitter & H. Weber (edit.). Autogestion or Henri Lefebvre in New Belgrade. Berlín: Sternberg Press, 2018.

Lefebvre, H. (2013). La producción del espacio. Madrid: Capitán Swing. Publicado originalmente en 1974.

Macdonald, D. B. (2002). Balkan Holocaust? Serbian and Croatian victim-centered propaganda and the war in Yugoslavia. Manchester: MUP.

Naef, P. (2016). Tourism and the “Martyred City”: Memorializing War in the Former Yugoslavia. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 14 (3), pp. 222-239.

Pavlowitch, S. (1988). The Improbable survivor: Yugoslavia and its problems, 1918-1988. Columbus, OH: University Press.

Popović, T. et al. (2020). Reshaping approaches of architectural heritage devastated through bombing: case study of Generalštab, Belgrade. Urban Design International, pp. 1-14.

Ribarevic-Nikolic, I., Juric, Z. (1992). Mostar ’92 Urbicide. Croatian Defense Council-Mostar, Public Enterprise for Reconstruction and Building of Mostar, Zagreb: IDP-Municipal Headquarters Mostar.

Rodríguez Andreu, M. (2021). Las movilizaciones sociales en el espacio posyugoslavo. Oportunidades políticas y estrategias contenciosas. Tesis para la obtención de grado en Doctor en Derecho. Universitat d’ Valencia.

Ronnenberg, K. (2018) “Henri Lefebvre and the question of Autogestion”. En: Sabine Bitter & Helmut Weber (edit.). Autogestion or Henri Lefebvre in New Belgrade. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Ruíz Jiménez, J. A. (2016). Y llegó la barbarie. Nacionalismo y juegos de poder en la destrucción de Yugoslavia. Barcelona: Ariel.

Selvelli, G. (2017). The Siege and Urbicide of Leningrad and Sarajevo. Testimonies from Lydia Ginzburg and Dževad Karahasan, Kongressakte von der Konferenz “Konteksti”, University of Novi Sad, S. pp. 501-512.

Smith, N. (2018). Preface. En: S. Bitter & H. Weber (edit.). Autogestion or Henri Lefebvre in New Belgrade. Berlín: Sternberg Press.

Staničić, A. (2021). Media propaganda vs public dialogue: the spatial memorialisation of conflict in Belgrade after the 1999 NATO bombing. The Journal of Architecture, 26(3), pp. 371-393.

Veiga, F. (2002). La trampa balcánica. Barcelona: Grijalbo.

Vidler, A. (1992). The Architectural Uncanny. Essays in the Modern Unhomely. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Weiss, S. J. (2000). NATO as architectural critic. Cabinet, vol. 1.

Žižek, S. El sublime objeto de la ideología. Buenos Aires: Siglo XXI. 2007.

Žižek, S. (2011). El acoso de las fantasías. México: Siglo XXI.

Descargas

Publicado

-

Resumen365

-

PDF454

Cómo citar

Número

Sección

Licencia

Derechos de autor 2022 Universidad Antonio Nariño

Esta obra está bajo una licencia internacional Creative Commons Atribución-SinDerivadas 4.0.

Portal de Ciencia Abierta

Portal de Ciencia Abierta